Meaning and Consciousness

Meaning does not necessarily entail any phenomenological consciousness, but consciousness might owe its emergence in part to meaning drawing it out.

Meaning does not necessarily entail any phenomenological consciousness, but consciousness might owe its emergence in part to meaning drawing it out. In order to substantiate this statement, we will take some time to review our conceptualization of meaning.

Basal meaning

At one scale, meaning is a practical process that living systems follow to live, setting and pursuing their goals within these lives. Living systems that do not have meaning do not maintain their structure and abilities over time in diverse environments. Here, meaning can be further broken down to some sub-functions: distinguishing between objects in the environment and attending to some over others, creating and maintaining memories, and self-reference. This version of meaning–basal meaning–breaks somewhat from the more folk versions of meaning.

Fast and slow meaning

At another scale–a human-centric one–meaning is a dynamical process in which we find ourselves presented with a phenomenal experience of a reality teeming with meaning. Objects with rich surrounding contexts (e.g., a teapot gifted to us by a loved one) are different from those lacking in context or with context that deprives them of meaning (e.g., a mass-produced teapot we bought from a popular online retailer). This is the immediate or "fast" sense of meaning. We also have a surrounding context that supports the day-to-day what-it-is like to be us. We do what we do not because we obey our bodies but because we are the central protagonist in a story that happens to feature our point of view at its heart. This narrative or "slow" sense of meaning allows us to set and pursue goals both clear and present or vague and distant. Fast and slow meanings form a circular dynamic, where an absence of one leads to an absence of the other.

Combining meanings

Looking at meaning from these two different scales–evolutionary, basal meaning; phenomenal, human meaning–we note many similarities but one key difference: consciousness. That is, the phenomenal i.e., experiential aspect of consciousness is clearly central to human meaning but is not present in basal meaning. Since we're treating meaning as a single phenomena with many faces, it is therefore necessary that we address this discrepancy. However, in order to do so, we are immediately confronted with one of the oldest puzzles of consciousness–why is it like anything to be anything? It is at least fortunate that we do not have to answer this question directly in any ultimate sense (i.e., resolving the "Hard Problem"), but we should address a narrower sense. In this narrower sense, we ask this: what is the value of consciousness versus non-consciousness is in living organisms? In other words, is consciousness useful and when and how is it useful? (For confusion avoidance, we will now refer to phenomenal consciousness as experience and its variations.)

The evolutionary value of experience has many candidate explanations. Simplest among these is that experience allows us to better pick out features in our environments. Yellow is as vibrantly yellow as it is because if it were less vibrant, we would not know to shift our attention (which involves physically shifting our eyes, a costly move) towards the (perceived) object that demonstrates the yellowness. If that object happens to be a fire, it's very good that its extreme yellowness can arrest our attention. Call this the sensory explanation.

Another plausible story from evolution is about decision-making in complex environments. The sheer number of possibilities for our intentional actions is too much to handle on any neurocomputational level. Instead, we get summary information in the form of feelings. Antonio Damasio's Somatic Marker Hypothesis explores this at length. In short, feelings allow us to shortcut complicated calculations in order to make important decisions under time pressure (which is all the time, with more or less time and/or pressure)[1]. Call this the decision-making explanation.

Both of the above explanations are plausible and compatible with one another. As expected, they don't prove themselves in any direct way–they are reasonable conjectures based on straightforward observations about conscious creatures (ourselves, gathered through self-reflection, reports from others, and observable behavioral measures). Though they are solid explanations, they raise some questions. Most pressing for us, these explanations say little about fractional versions of experience. Do really simple organisms (like single cells) still need to pick out features in their environments? Yes. If that's all you need to exert pressure on experience's emergence, we ought to expect experience at basal levels. Simple experience, yes–but experience (i.e., consciousness). This applies both to the sensory explanation and to the decision-making explanation. If either or both are accurate, experience is everywhere life is found.

I don't have a problem with this upshot, as it both motivates and supports a form of panpsychism that I (loosely) espouse, if not fully endorse. For the sake of the discussion, we will assume that there's something to this, that sensory and/or decision-making pressure has resulted in rich kinds of qualitative experience. Where does meaning fit in?

It should not go unnoticed that the pressures for experience to emerge are themselves related to basal meaning. In order for an organism to more effectively pursue its meaning within its environment, we (and likely many other organisms) further developed experience. In other words, consciousness emerged naturally from the pursuit of meaning. This is at least the case in the human story but it might not be the case for all organisms, at least not to the same extent. Organisms all have some sense-making and decision-making and wherever these are present we ought to expect at least some experience to be present–unless of course there are other mechanisms that step up to allow the organism to successfully navigate the same problems that experience helps navigate. For example, AI seem to be able to solve all sorts of puzzles and games without the clear evolutionary pressure pathway that would have selected for experience.

At this point, it is broadly assumed that AI is in no way phenomenally conscious. I share this assumption, for various reasons[2]. The reason most relevant here is that there's no reason to suspect that general problem-solving abilities are meaningful in the sense we've explored. Today's AI does not have self-reference, memories, or attention, even though some systems exhibit weak copies of these. Instead, today's AI has taken alternative paths to competency in extremely narrow tasks. This is not to say that AI must follow our and other living systems' examples to be truly great at being useful but that we have no reason to suspect that meaning and therefore experience would naturally emerge from this high-level, problem-solving goal.

Experience through selection

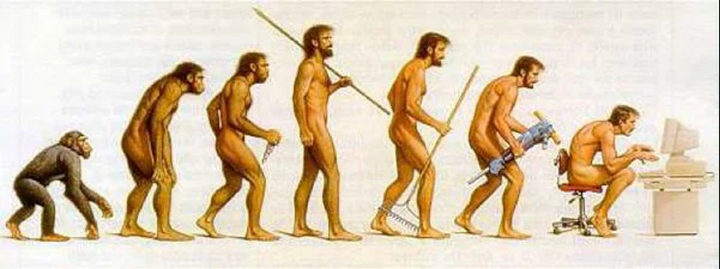

We are now in a better position to address the original question of meaning synthesis–how do we get from basal meaning to human meaning? Very loosely, the process could be something like this:

- The organism finds itself in a complex, demanding environment

- Evolution selects for novel and diverse senses / more advanced decision making to survive in that environment

- Experience (i.e., phenomenal consciousness) emerges as a useful tool, exerting selection pressure

- New abstractions like complex language further the organism's ability to pursue meaning in diverse environments, exerting selection pressure

- Cultural adaptations formalize and help structure particular meaningful trajectories, exerting selection pressure (but now at short timescales that limit genetic pressures but allow for other pressures, like memes)

The central idea is that, as simple organisms scale up their bodies and goals and the complexity of their environments, phenomenal experience naturally emerges. This continues even as that organism grows to human/humanity scale. Simple goals, memories, self-reference, and attentional shifts are conserved but complex goals, wider-reaching memories, self-other relations (i.e., theory of mind), and volitional attentional shifts (i.e., free will[3]) are piled on top of those to produce modern day humans, beings thrown into a world full of meaning.

It is in this sense that meaning can be said to beget consciousness. While it's unclear whether there are non-natural mechanisms that lead to consciousness (IIT would predict this), consciousness as we know it owes its emergence to basal meaning giving it a home. In short, consciousness is a tool that helps us better navigate the increasingly complex world and meaning is the machinery that benefits from its presence.

Final thoughts

- We addressed phenomenal consciousness but largely ignored other kinds. Each of these can be addressed from this meaning approach, though we will not do so here and now. For example, wakefulness (being aware and having executive control) is very clearly useful to basal meaning. It lets you shift attention, plan out complex behaviors, and perform abstractions. Phenomenal consciousness was addressed because of its assumed absence in basal meaning versus human meaning.

- Theories of consciousness are largely interchangeable in this account. One of the most fundamental things (some might say the only thing) we know to be true is that there is something that it's like to be us. Once we adopt the view that our experience is dependent on the goings on of the universe, it is just[4] a matter of figuring out how and in which ways experience changes as we shift parameters around us. These theories are of value insofar as they help us do this. Their ultimate truth or completeness are unimportant.

- Admittedly, the definition of meaning we're working with differs from the broader one used in other spaces–however, even the very different ways the word is wielded share a common underlying concept. The alternative–creating a new term (μing) or resurrecting an old one (eudaimonia) for our cause commits us to an unnecessary separation. Meaning is central to living organisms and science should recognize this.

Footnotes

As is the case with anything branded a mere "hypothesis" in science, the somatic markers hypothesis remains in this state due to arguments against it. These debates run deep but I don't see that they fundamentally undermine the basic notions of the hypothesis–that attaching feelings to perceptions can facilitate decision-making. ↩︎

Besides the meaning-centric reason explored here, other decent theories of consciousness present compelling reasons to doubt AI experience. Integrated Information Theory (IIT) suggests that current methods can produce a near-philosophical zombie because the observable functions of an AI can still be present with extremely minimal integration (and therefore consciousness). Global Neuronal Workspace (GNW) theory expects a specific set of modular components that work together to form consciousness, which would be absent in any AI that wasn't designed to exactly emulate these components (i.e., all AI in practice). In fact, it's only the most dedicated functionalist reductionists that would assume consciousness comes along for the ride. These few are often themselves deeply involved in and motivated by building AI systems–consequently, they are not in the business of building rigorous theory to support their views. Their right, but the Laissez-faire attitude to AI consciousness is probably not without consequence. ↩︎

"Free will" is used here to refer not to some ultimate freeness of will but rather a local experience of free will and the kinds of unique behavioral outcomes it can produce. ↩︎

Said semi-facetiously. This is a problem but we don't need to solve it fully. Just a bit, which we haven't done all that well, in spite of ourselves. ↩︎